Published in: Kokiri Issue 5 - Whiringa ā Rangi - Hakihea 2007

Te Puni Kōkiri’s report Māori in Australia - Ngā Māori i Te Ao Moemoeā gives the most accurate picture of how many Māori live in Australia, why they went there, and how they’re faring. The report also highlights that even though Māori are living and working in another country, they still identify as Māori and most still call New Zealand “home”.

Paul Hamer, Te Puni Kōkiri Policy Manager, wrote the report based on research he did in 2006 as visiting fellow in the Department of Politics and Public Policy at Griffith University in Brisbane.

Paul’s research included a 50-question online and self-administered survey of 1,205 Māori from across Australia. The views of another 400 Māori were included from other fieldwork.

Topics covered include the history of Māori contact with Australia; the reasons Māori move across the Tasman; the jobs they are doing; and their integration into the Australian state through, for example, their take-up of citizenship.

The research also explored their attempts to build community infrastructure and maintain their culture; their sense of being different from Māori in New Zealand; and the challenges that go with being Māori overseas.

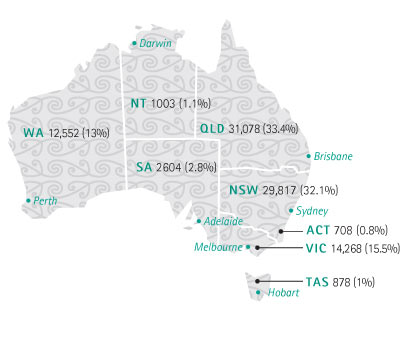

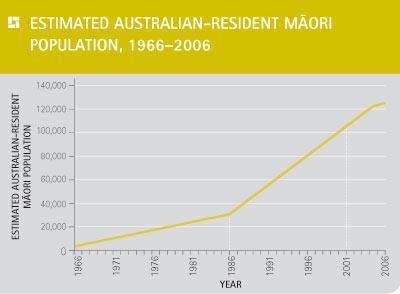

The 2006 Australian census revealed that 92,912 people stated Māori ancestry among their first two ancestry responses, a 27.4 percent increase from 2001. However, the Te Puni Kōkiri research suggests that this census probably understates the Māori population and between 115,000 and 125,000 Māori may be living in Australia.

Paul explains, “Some 14 percent of survey respondents stated that despite their strong sense of Māori identity, they would not enter ‘Māori’ at the census ancestry question, preferring to enter descriptors like ‘New Zealander’ or ‘Australian’ instead.”

Māori in Australia: Key Findings

Reasons for moving

Māori migration to Australia largely follows the pattern of overall New Zealand migration. The majority of survey respondents said they had moved to Australia “for a better chance to get work or better job(s)“. Most respondents also said they had come “for a new start in life“. Specific reasons included “pull factors“, such as better weather, higher wages, or joining whānau already in Australia; and “push factors“ such as negative experiences in New Zealand arising from social dysfunction and perceived prejudice.

Employment

Nearly 87 percent of survey respondents said their employment had become “much“ or “a bit“ better since moving to Australia. Many said that Māori in Australia have a reputation for hard work. Occupations pursued by Māori in Australia include entertainment, shearing, mining, construction and security. Census results also showed Māori workers in trades, clerical, machine operating roles, and labouring.

Political participation

Māori have a very low rate of take-up of Australian citizenship – in 2001 it was 22.8 percent. Because of this, most Māori in Australia cannot vote. Just under half of the survey respondents who had not become citizens said they wished to remain a citizen of New Zealand only. Thus Māori in Australia often continue to look to the New Zealand Government or iwi organisations for support, including for funding and services.

Retention of culture

The report noted a fascination many Australians have with Māori culture. Indeed, Māori cultural performances in Australia play an important role in promoting New Zealand. Key issues for Māori in Australia include the small number of kaumātua; the cultural challenges of holding tangihanga in the absence of marae or other communally owned buildings; and the loss of traditional knowledge.

The role of whānau

Many Māori in Australia respondents commented that they missed their extended

whānau structure. Some said they had taken on new notions of “whānau“. More than 60 percent of respondents defined whānau as including “family and relatives plus other Māori you live and/or work and/or socialise with in Australia”. A further 52 respondents ticked “other“ and broadened their concept of whānau beyond even Māori. There was evidence that Māori are bonding very well with Pākehā and other New Zealanders in Australia, which shows the strength of New Zealanders’ national identity overseas.

Te Reo Māori

A range of formal opportunities exists for learning te reo in Australia, from pre-school to adults, but skilled teachers are scarce and there are other barriers to successful learning. While many M

āori in Australia feel the need to learn te reo more than they ever did in New Zealand, interviews and census results suggest that use and knowledge of te reo Māori in Australia have been steadily declining.

Returning to New Zealand

A high proportion of Māori indicated that they will return to New Zealand, or at least intend to return. Māori in Australia – despite it being a country to which New Zealanders tend to migrate permanently – are much more set on returning to New Zealand than predominantly professional

Pākehā New Zealanders spread throughout the world (as revealed by the 2006 Kea survey). In other words, Māori overseas appear to feel the pull of home more strongly than other New Zealanders.