Governance in its widest sense refers to how any organisation, including a nation, is run. It includes all the processes, systems, and controls that are used to safeguard and grow assets.

Last updated: Wednesday, 10 August 2022 | Rāapa, 10 Hereturikōkā, 2022

What's on this page?

When applied to organisations that operate commercially, it is often termed "corporate governance" and has been described by the World Bank as "promoting fairness, transparency and accountability" and by the OECD as "a system by which business organisations are directed and controlled".

The principles of governance apply to any organisation, whether it the biggest multinational company or a small whānau trust in a remote part of New Zealand.

In Māori organisations, the objectives of governance will take into account the way in which Māori relate to the assets and what they are used for. In some instances, although the organisation operates commercially, commercial objectives may be balanced with the need to safeguard the assets for future generations.

Tikanga principles may also be put into practice in the board of a Māori organisation alongside governance principles. Tikanga, kawa and values that meet the aspirations of iwi, hapu and whanau often give direction to board work. Tikanga can easily fit alongside governance best practice.

Three organisations committed to good governance in New Zealand, the Institute of Directors in New Zealand, Securities Commission of New Zealand and the New Zealand Stock Exchange have all published detailed guidelines on the principles of governance and the responsibilities of boards.

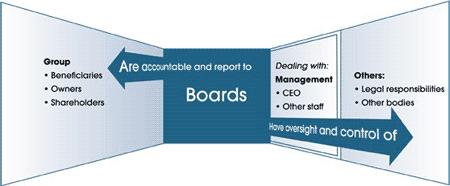

As you can see from the governance diagram below, boards are the critical link between the aspirations of iwi, hapu, whanau and shareholders and the way an organisation is run day-to-day.

Why governance matters

Governance in its widest sense refers to how any organisation, including a nation, is run. It includes all the processes, systems, and controls that are used to safeguard and grow assets.

Governance diagram

This diagram shows the relationship between the owners and people who benefit from an organisation, its board, and the management.

This diagram shows the relationship between the owners and people who benefit from an organisation, its board, and the management.

Extra dimensions for Māori organisations

Although good governance principles and practices are universal, no two organisations are ever the same. There are also particular characteristics of Māori organisations which bring extra dimensions to the practice of governance.

Governance for Māori organisations may require consideration of the following:

Purpose of the organisation: Many Māori organisations have multiple purposes. This means that they are not set up just to make a profit. Many have to balance being financially viable with the social and cultural aspirations of the owners as their core purposes. Although the organisations may trade commercially and measure themselves against economic indicators, wealth creation is not seen as an end in itself.

In setting up and selecting the type of legal structure for an organisation, it is important to clearly know the intended purpose of that structure. For example, if Māori land is the core asset, because this land will never be sold, for either legal or tikanga reasons, the organisation will not be able to make trading decisions following usual commercial models. This can make running a Māori organisation particularly challenging.

The importance of tikanga and values: Tikanga principles are often put into practice in the board of a Māori organisation alongside general governance principles. Many Māori organisations are explicitly driven by tikanga, kawa and values (for example in employment, tangihanga and cultural leave policies) that take into account the aspirations of whanau, hapu and iwi. Cultural considerations will sometimes take precedence over purely economic factors (for example building in close proximity to urupa or recovering debts from relatives).

Māori organisations may also have a Māori dimension in procedure such as the use of Te Reo, mihi, karakia, koha, hospitality for manuhiri, manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, consensus decision-making and regular consultation hui. These elements should support the general principles of good governance. It can be important to have people with expertise in tikanga and kawa on the board.

Long-term view: Many Māori organisations have an extremely long-term view of their future. This has implications for many aspects of governance such as selecting board members with a view to handing the business on, and in strategic planning where a 25 year view, or even more, may be taken.

Some stakeholders, including people providing finance, may take a short-term view, for example focusing on immediate and short-term returns or only thinking in terms of a five year planning cycle. Good communication with stakeholders and potential financiers about the strategic plan is therefore recommended to ensure that any long-term view is well understood.

Taking a strategic long-term view can also help organisations avoid being locked into bad deals or prevented from taking up opportunities that may arise in the interim. Ensuring that there are "off ramp" or exit strategies can help to offset the effects of bad deals or allow the organisation to take up new opportunities as they arise.

Appointment of board members: This can be a particularly challenging area for Māori organisations. Rather than a strictly business skill base, board appointments in Māori organisations may be influenced by the requirements of the specific structure of the organisation (say a trust under the Te Ture Whenua Act), by an election process (for example a Māori Trust Board) by whakapapa and tikanga requirements (a rangatira or respected elder), whanaungatanga (a relative), or because of expertise in other fields (i.e. business/financial skills/qualifications).

If a board for example cannot find all the skills in one person, the board may balance people who are appointed for business skills and others for their tikanga skills. There is a perception that the pool of "experts" is small, especially for those who have expertise in business and finance. Transparent appointment processes are recommended and help to avoid allegations of appointing relatives to key positions. Quality control issues are also important and can be helped by advertising vacancies, candidate vetting, education/training of existing board members, regular board member rotation, annual assessment/audit of performance and procedures for removal of board members in the event of non-performance.

Board dynamics: The dynamics around the board table of a Māori organisation can be influenced by factors such as the multi-purpose nature of the operation, the importance of tikanga and values, a long-term view, appointment of board members, owner involvement, restrictions on commercial use of assets and use of Māori terms. All this can make the board dynamics of a Māori organisation more challenging.

The need for managing the board dynamics through good governance, leadership and transparency is vital. Good communication is therefore crucial. This includes directors and trustees asking questions to be sure they have a good base of understanding for making decisions.

Involving owners in decision-making: Boards of Māori organisations may be required to undertake a higher level of consultation, even in commercial decision-making, than in non-Māori business. For instance, a board may be expected (or required by law) to go back to owners on an investment decision for approval.

Reporting can be cumbersome and conflict can arise at board level if appropriate consultative processes are not followed. The additional delay and lost opportunities need to be balanced with any requirements to consult. Factors to be taken into account include consultative burnout (many Māori have been all hui'd out resulting in poor attendance levels) and commercial opportunities lost as a result of delays. A good board will find the appropriate balance.

Commercial use of assets: Many Māori organisations have restrictions on the ability to use their core assets. Those restrictions can be imposed by law (legislation or core legal documents such as a trust deed) or by the owners (in accordance with tikanga such as an aversion to sell ancestral land or use it as security).

Such restrictions can lead to problems in dealing with financial organisations (particularly trading banks) who usually require security before providing finance.

Māori organisations may also have problems finding financial organisations prepared to accept Māori freehold land as security for lending, especially where Māori freehold land is the core asset.

In such situations Māori organisations may have major difficulties achieving their purposes, particularly if those purposes include developing the land and/or creating financial returns for the owners.

The Treaty of Waitangi: Many Māori organisations refer to the Treaty of Waitangi in their mission/vision statements and core legal documents. Such statements also include adherence to the "principles of the Treaty of

Waitangi". Boards need to be clear about what this reference actually means as far as governance is concerned as they could be held to account in the event of non-compliance.

Use of Māori terms: The use of Māori terms (Māori language in English language deeds, constitutions, statutes and legal documents) can lead to difficulties in interpretation. The recent lengthy litigation involving the definition of "iwi" is a classic example. Clear definitions/translations of key Māori terms may be required to ensure that confusion (and unnecessary litigation) is avoided.

Business Failure - Public Relations: A significant number of businesses and organisations fail for a whole range of reasons. Poor governance can be a fundamental cause. Māori organisations have come under particular scrutiny. Ensuring that good governance is followed goes a long way to reducing the odds of failure and any negative fallout as a result.

Types of Māori organisations

Although the structure and ownership of an organisation will influence some elements of governance, the basic governance principles remain the same across all organisations.

A report on Māori organisational governance notes that some structures suit some purposes better than others. Groups have selected structures to fit their ownership structures, asset base, and goals. Organisations may also change their structure for different stages of development.

Some groups may even consider multiple structures for different needs — for example having one structure to deal with social/cultural “business” and another for the trading or commercial side of the operation.

These are the main legal structures used by Māori organisations operating on behalf of multiple owners. Some have links to case studies of successful organisations operating through them.

- Partnership

- Company

- Charitable Trust

- Incorporated Society

- Māori Trust Board

- Trust

- Structures under Te Ture Whenua Māori Land Act 1993

- Māori Reservation

- Māori Incorporation

It is essential to consult a lawyer on the type of structure most suitable for a particular purpose, and on the legal requirements for a particular structure.