Jock McEwen (b.1915 – d.2010) cannot be called “a man of his time” because during his time paternalistic and assimilationist views were still widely held.

Published: Thursday, 8 December 2016 | Rāpare, 08 Hakihea, 2016

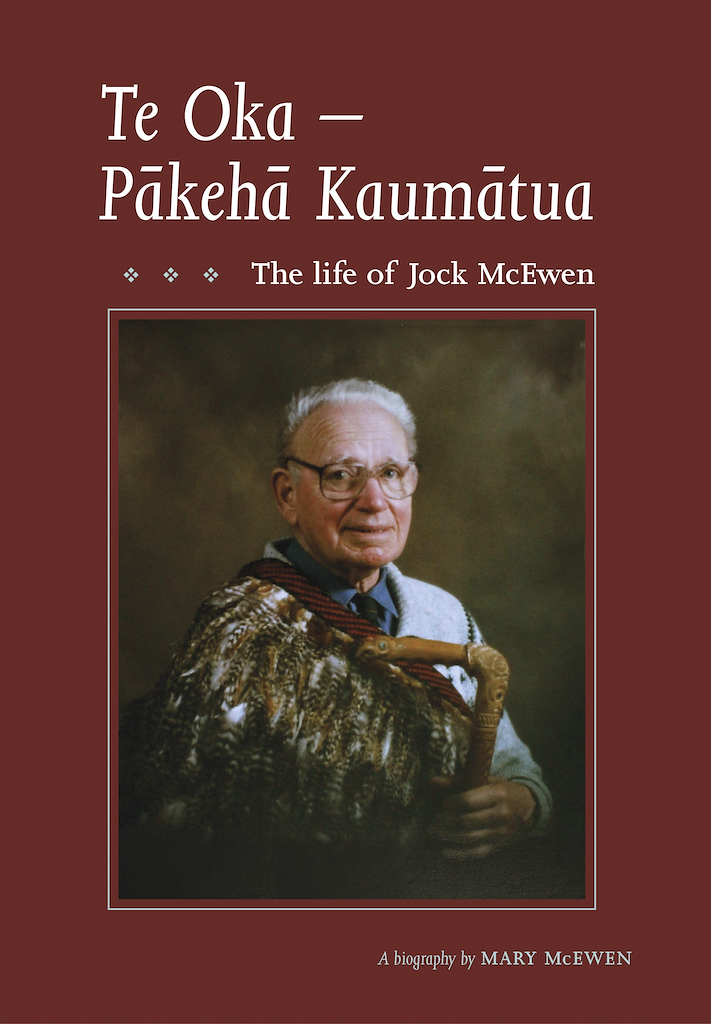

Launched at Ōrongomai Marae in Upper Hutt, Wellington, the biography, Te Oka – Pākehā Kaumātua: The life of Jock McEwen recounts the remarkable life of Jock (Te Oka) McEwen, a career public servant who worked for 40 years in the Native Affairs (later Māori Affairs) and Island Territories departments.

Of mainly Scottish ancestry, some of his tīpuna arrived in Aotearoa as early as the 1840s. His mother’s kuia spoke only Gaelic when she arrived at 14 years old. She learned Māori – from the locals in the neighbouring village of her home in Kaiwharawhara – before she learned English.

Te Oka grew up in the Manawatū and attended Taonui School in Aorangi where his dad was principal. It wasn’t a Native School, but it was just down the road from Aorangi Marae so lots of locals there too. Māori language was encouraged by his whānau and Te Oka enjoyed playing with his Māori friends, visiting their marae and learning from their elders – one of whom was Meihana Te Rama-Apakura Durie and his wife Kahurautete.

Jock was interested in Pacific cultures and had a gift for languages. He wrote notes about things he learned. He collected papers, whakapapa (his own and others) photographs, mōteatea, newspaper articles, letters and the like. He published what he learned in books such as Rangitāne: A Tribal History and the first Niuean dictionary. Through his research and experiences, Jock formed his own ideas and contributed to scholarly works such as the 6th Edition of the Williams Dictionary. He was president of The Polynesian Society for over 20 years. Jock was part of the original management committee that started the Te Ao Hou magazine series in the early 1950s.

But it wasn’t just intellectual pursuits that interested him. Jock liked to do things and was creative. He played music, wrote poetry and composed songs. Encouraged by his whānau, he taught himself to carve at an early age – a passion that would last through-out his life. Jock’s work adorns whare at Pipitea Marae, Kohunui Marae in the Wairarapa, the Michael Fowler Centre and Ōrongomai Marae where he ran his own carving school.

Jock McEwen didn’t identify himself as Māori. He spoke Māori, had a passion for carving, composed waiata, collected whakapapa, and was personal friends with great Māori leaders – but he didn’t want to be Māori. He understood the Māori world because he engaged in it and was interested.

Upon retirement in 1975, Jock McEwen had been Secretary of Māori Affairs (the equivalent of the present-day Chief Executive role at Te Puni Kōkiri) for 12 years and before that held the position of Secretary of Island Territories. Like many involved in kaupapa Māori, Te Oka was often absent as his tamariki were growing up. The biography Te Oka – Pākehā Kaumātua is written by Jock’s daughter-in-law, Mary McEwen. Mary was a finalist in the 2006 Montana Book Awards for her first biography on her own father, Sir Charles Fleming. Mary’s work is clearly thoroughly researched and presents a warm, yet unbiased picture of the man, and an important history of the times.

Jock’s legacy of contribution to Māori and the people of the Pacific continues with over 400 secondary schools receiving copies of his biography through a grant from the Stout Trust, facilitated by Friends of the Turnbull Library. Produced in hardback, copies of the book are available this Christmas for $49.95 online at Potton & Burton publishers.