We remember the fallen of World War I. The New Zealand Government developed a programme to mark the First World War centenary from 2014-2018. The WW100 programme aims to foster appreciation and remembrance of how the First World War affected our nation and its place in the world both at the time and beyond.

Just over 100,000 New Zealanders served overseas, from a population then of barely one million. Of those, more than 18,000 died and over 40,000 were wounded. Most were young men, and nearly one in five who served did not return.

The events of 1914-1918 affected more than those who served overseas – they touched nearly every New Zealand family, every community, school, and workplace. In nearly every New Zealand community, large or small, have a memorial marking the First World War. In many marae and dining halls a Roll of Honour reminds us all of the contribution of Ngāi Māori to the war effort.

First World War Centenary Panel member Dr Monty Soutar, historian and author of Ngā Tama Toa: The Price of Citizenship reflects on the events which led to the establishment of the Māori Contingent/Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū and offers some whakaaro that we might bear in mind as we look ahead and beyond the centenary programme.

Published: Wednesday, 22 April 2015 | Rāapa, 22 Paengawhāwhā, 2015

Māori in the First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War a request by Māori leaders for a unit based on ethnicity was not at first permitted. Māori could, however, enlist individually for service in other units within the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) and some did.

When it was learnt that Algerian and Indian troops were on their way to the seat of war, the five Maori parliamentarians made a second appeal in the House. This time they were successful, Prime Minister Bill Massey reminding parliament, “Our Māori friends are our equals in the sight of the law. Why then should they be deprived of the privilege of fighting and upholding the Empire?”

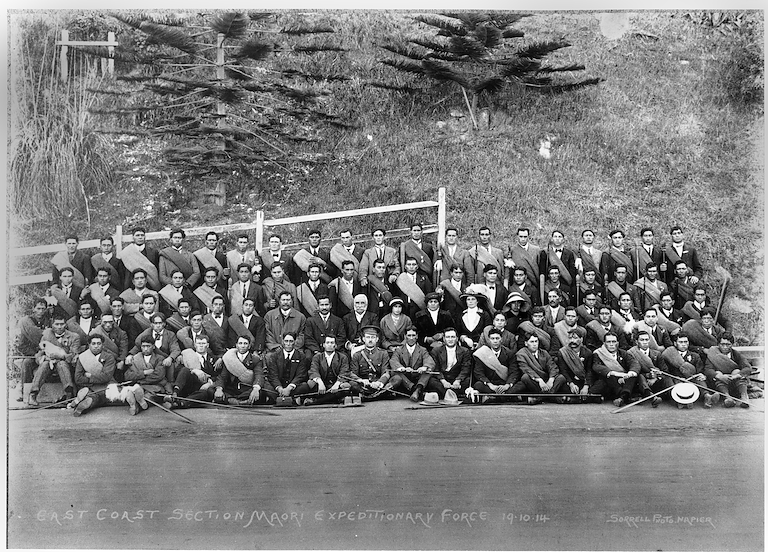

Within a month the volunteers for a 500-strong Māori Contingent had been selected and from 17 October 1914 tribal detachments of young men began arriving at Avondale Racecourse where the unit was to be trained. It was the East Coast-Gisborne detachment who brought with them the name Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū (the seventy twice-told warriors of the war god Tū), that would be adopted by the Contingent. Wi Pere, one-time MP for the Eastern Māori electorate, gave the name.

The detachments were the pick of their tribe’s youth, and while a handful had received little schooling, the great majority were well educated ―the product of the church colleges.

Most recruits were between the required ages 21 to 40, but some had slipped through who were outside those limits.

The tribal responses to official calls for volunteers varied dramatically. Iwi who had suffered land confiscations less than half a century before still included members who had fought in the wars of the 1860s. Land loss, denial of access to resources and associated poverty were all leading causes for lower recruitment among these iwi during the First World War.

By the New Year the Māori Contingent was a well-drilled and impressive military unit. Their training in New Zealand ended on 14 February 1915 and the unit set sail for Egypt. They served first as garrison troops on the island of Malta before transferring to the Gallipoli Peninsula. They gained a reputation as fierce fighters during the August offensive, but alas, by September their numbers on the peninsula had been reduced to sixty.

After the defeat of the Allies at Gallipoli the Māori Contingent was reinforced and sent to the Western Front as a Pioneer Battalion (ie trench diggers and road builders). During the First World War 2000 more Māori and Pacific Islanders served with the NZ Pioneer Battalion which in1917 became known as the Māori Pioneer Battalion. They returned to New Zealand in March 1919.

The individual who best understood the position of Māori in New Zealand society after the war was Sir Apirana Ngata. Involvement in the war, he said, had brought Māori into contact with Pākehā soldiers, culminating in a stronger understanding and respect between the two afterwards. Māori returned soldiers carried a wider world view back to their tribal communities and this also motivated the young through the many and varied patriotic institutions and commemorative events such as Anzac Day, which were reinforced by the native schools. The returned men were responsible for the broadening of the Māori outlook on the world and for the appreciation and interpretation of events abroad between the two world wars. They understood and indulged the spirit which moved their sons in the 28th Māori Battalion to venture where they first broke the trail.

The First World War (the ‘Great War’) was supposed to be the war to end all wars. Within a generation, however, the world was at war again and every year since, there has been a significant conflict occurring somewhere around the world. These days, the present conflicts in Ukraine, Israel-Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Thailand, South Sudan, Libya, Afghanistan, South Yemen, Somalia, Yemen, Northern Mali are thought to be some kind of aberration. These wars reinforce the counter-myth that peace is not the societal norm and unfortunately it appears conflict is a regular feature of human existence.

Projections today show that the median age of Māori in 20 years’ time will be twenty-five years old ‒ which will be half the median age of Pākehā. Therefore, it is likely in future conflicts around the globe more young Māori could be called on to play a significant role in our Defence Force on behalf of New Zealand.

There is also the personal conflict that everyone faces right now, how to make something more of one’s life. Given the opportunities that previous generations have left us, by risking their own lives to ensure our freedom, ought we not to do our best to live in a way that honours them? The sacrifices of our ancestors should remain valid as a warning to us. We should never forget their lessons and do as our ancestors have done since time immemorial. Heed their ancient call and gird our loins for the challenges ahead.

“Whangai piri, whangai rata, humeia taku maro!”

“Tighten my grip, sharpen my weapon point, fix me in my battle dress!”

Karakia of Tūtawake preparing for battle, son of Tangaroa and Houmea - from the Writings of Mohi Ruatapu.

Photo caption: Gisborne-East Coast volunteers for Māori Contingent. This photo of the detachment was taken in Napier on 19 October 1914. Apirana Ngata can be seen seated in the centre alongside Mayor Vigor Brown, Arihia Ngata and Lady Carroll.

About the author: Monty Soutar (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Awa) is a senior historian for the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, and Auckland War Memorial Museum’s World War One Historian in residence. Monty oversaw the build of the 28th Māori Battalion website, developed on behalf of the 28th Maori Battalion Association by Manatu Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage and Te Puni Kōkiri. In November 2014, his book Ngā Tama Toa: The Price of Citizenship was published in te Reo Māori as Ngā Tama Toa: He Toto Heke, He tipare here ki te ūkaipō.