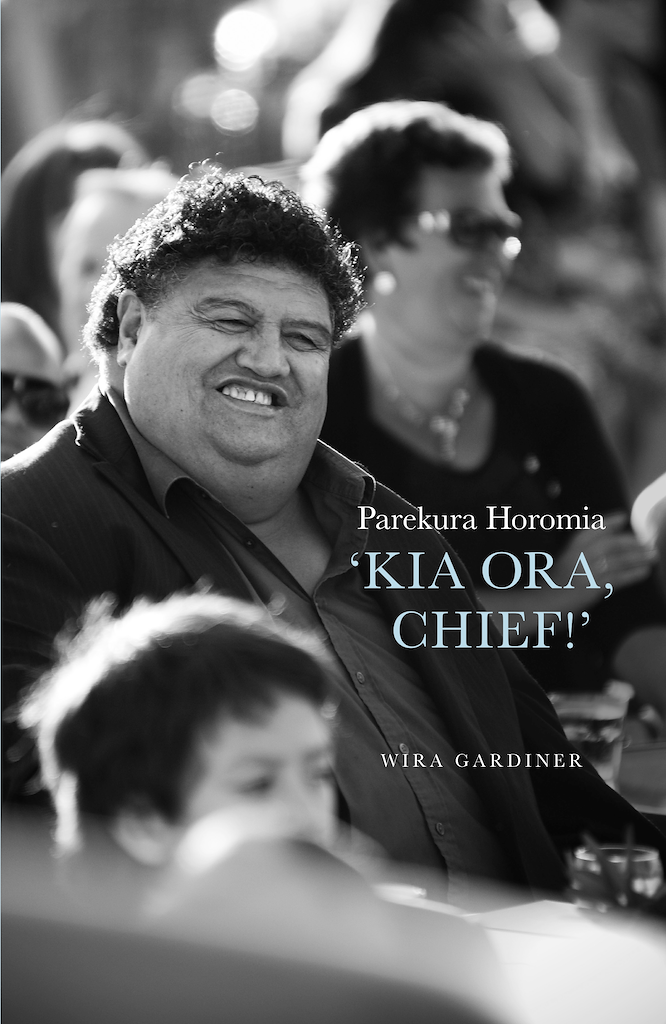

Kia Ora Chief is a new biography of the larger-than-life former Minister of Māori Affairs, the late Parekura Horomia. It is written by former Te Puni Kōkiri Chief Executive Sir Wira Gardiner.

Kōkiritia talks to Wira about the background of the book and publishes an exclusive extract looking at events that led to Parekura becoming a senior bureaucrat.

Published: Thursday, 4 December 2014 | Rāpare, 04 Hakihea, 2014

Kia ora Chief, is a greeting synonymous with the larger-than-life former Minister of Māori Affairs, Parekura Horomia who died in April last year.

Parekura and his wife Gladwyn at Koro Wallace Kaa's house in Wharekaka, 1969. Source: Horomia whānau

Now it is the name chosen for his new biography to be launched at Tolaga Bay this weekend, and again next week at Parliament. The biography covers his life from growing up on the East Coast, the variety of his early working life, his parliamentary career, and even his tangi in Tolaga Bay attended by an estimated 12,000 people from all walks of life.

Author Sir Wira Gardiner, a long-time friend and ‘firefighter’ says the book has its roots in 2006.

“I said to Parekura, ‘you know someone should write your book because you are an example of what’s possible,’” Wira explains.

“He asked me if I would write it and I said ‘OK, I’ll write it but I need to see all your diaries and all your notes’. Of course, he didn’t have any. He had speeches, but he never gave them.”

Wira then suggested he spend a few minutes a day dictating notes and getting them transcribed. ‘I’m right on to it,’ the then-Minister replied. But it never happened. In 2011, after the Government had changed, he told Wira that he was ready to write the book.

“I said to him ‘No, it’s bloody too late. You’re fish and chip wrapping now, you’re a yesterday’s man like me.

“I felt stink about that. So when I gave the eulogy at his tangi, I made a promise to his sons that I would write about his life. I forced myself into a discipline at the time by announcing that I would produce the book before the hura kōhatu. So that essentially gave me a year to 18 months.”

Wira says the difficulty at first was that people didn’t want to talk to him.

“It was too soon, they weren’t ready to talk about him. It took until the end of the year for people to start talking to me.”

Most of the 70 or so interviews, each lasting about an hour, were conducted earlier this year before Wira sat down for four months of writing – between 5 and 10 hours most days.

It was a labour of love for Wira, who fitted the writing around a large number of governance roles. All profits from the book are being directed to an education fund for Parekura’s mokopuna.

Did he learn anything new about the man he had known, and worked closely with for more than 30 years?

“How intensely private he was. He basically kept his life compartmentalised, even to people closely around him. So I knew most of his life, but I didn’t know about 30% of it. I found aspects of his life that really surprised me. Every corner I turned in an interview I found out something new.

“But percolating through all of them were consistent themes. Similar to at his tangi. Someone would stand up and tell a Parekura story and everybody would laugh because they would know the same story just with different names and dates. He could connect people by their interactions and relationships with him,” Wira concludes.

Extract from Kia Ora Chief

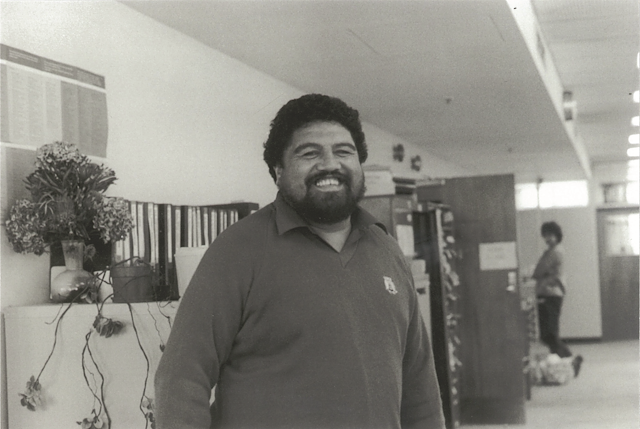

On face value, it is hard to imagine how Parekura became a senior bureaucrat. While there was no doubting his energy and determination, he certainly did not fit the image of a public servant. He lacked formal qualifications. His physical presentation was intimidating and unkempt, and his ability to express himself clearly and succinctly was limited. An unusual set of circumstances was required to catapult Parekura into the limelight; that and a special kind of senior bureaucrat, who was willing to look past these obvious deficiencies.

Parekura at GELS office, Department of Labour, Charles Fergusson Building, 1984 Source: Horomia whānau

The set of unusual circumstances took the form of the sweeping set of economic reforms ushered in by Roger Douglas[1] the Minister of Finance for the Fourth Labour Government. ‘Rogernomics’, as these policies became known, saw wholesale restructuring of the way in which government delivered services. By and large, rural New Zealand and the more isolated areas of Northland and the East Coast bore the brunt of these changes. On the East Coast, there were massive job losses in forestry, the Ministry of Works and other state agencies. To counter the job loss and the lack of opportunities for employment, the Labour Government introduced a range of employment schemes.

In 1978, Parekura returned to Tolaga Bay and got involved in farming, fencing, shearing, land management and a range of other community activities, including representing the New Zealand Māori Council at the local level. In 1978 and part of 1979, he worked with Boydie Donald’s[2] shearing gang. Boydie recalls that ‘he could shear a reasonable number of sheep in a day; his tally would have been about 300 sheep’.

Parekura’s first mission on returning to Tolaga Bay was to get back the farm, which had been sold by his Nanny, Mum Jane.[3] Alice (Tuppence) Smith[4] explained that her parents gave her the farm as a wedding present, but because of a violent marriage, she did not want to stay and moved to a house in Tolaga Bay. Mum Jane then sold the farm to a local for a token sum. Parekura went to the Māori Land Court to get the farm back. He was in his early 30s when he succeeded. Tuppence recalled that this was just before he started work with the Department of Labour. The land on which the house stood and the land around it belonged to his grandfather, Poneke (Nunu) Waikari.[5] Other parcels of land belonged to Nanny Sue Kirikiri[6] and other relations. The shareholders all agreed to give the land to Parekura, and he had won the first of many battles he was to wage over the next decade to take back control of Hauiti lands.

1997 CEG conference, Tikitere, Rotorua L-R John Bishara, Parekura, Dave Wilson, Richard Brooking, George Kahi, Hemi Toia. Source: Horomia whānau

By the early 1980s, he was employed by the Department of Labour as a Supervisor for the Project Employment Programme (PEP)[7] schemes for unemployed workers.[8] The PEP scheme began in August 1980 and ran for six years until August 1986, although it continued beyond this time in some rural areas, including the East Coast as a consequence of damage caused by Cyclone Bola in 1988. The scheme was designed to give subsidised, short-term public sector employment for job seekers who were at risk of becoming long-term unemployed. Parekura led work gangs throughout the East Coast on a variety of community enhancement projects ranging from chopping and providing firewood for older people to marae renovation projects. The PEP schemes were a heaven-sent opportunity for isolated communities throughout the country to renovate marae and complete other long-standing tasks. Workers on these projects learned basic carpentry skills, and some even became competent carvers. Just as importantly, they learned basic job skills, such as getting up each day to go to work and participating in positive community activities.

The second significant event that catapulted Parekura into greater prominence in the eyes of senior bureaucrats in Wellington was Cyclone Bola, which hit the East Coast in early March 1988. Cyclone Bola was one of the most destructive cyclones to ever hit New Zealand. As it moved over the Hawke’s Bay and East Coast, it slowed, and for three days, it dumped a huge volume of torrential rain on the region. Some of the worst-hit areas lay inland from Gisborne, ‘winds forced warm moist air up and over the hills, augmenting the storm rainfall. In places, over 900 millimetres of rain fell in 72 hours, and one area had 514 millimetres in just a single day.’[9] The floods that followed destroyed houses, crashed over stopbanks, swept away bridges, fords and roads and gouged out large sections of forested hillsides. Part of Gisborne’s water supply system was destroyed. There were three fatalities in Mangatuna. Thousands of people were evacuated from their homes in Gisborne and some hundreds in Wairoa and Te Karaka.

Ray Taylor[10] was heavily involved with recovery work resulting from the cyclone. He was the main point of contact for the Department of Labour. He and Parekura were responsible for organising 300 PEP workers, who turned up the day after the storm. The workers assembled at the Railway Reserve, Gisborne. The Department of Labour funded all the gear, the wages and the work vans. Parekura’s extensive network throughout the East Coast, his no-nonsense reputation and his links to key organisations, such as the New Zealand Māori Council and the Māori Women’s Welfare League, contributed to his growing reputation as a fixer and go-getter. He was someone who could get things done. He was 38 years of age. He had demonstrated that in times of great emergency and crisis, he could make things happen. This would have impressed the senior officials of the Department of Labour.

When I interviewed Mike Williams[11] who was President of the Labour Party from 2000 to 2009, he told me of a conversation he had with Parekura about the impact of Cyclone Bola on the East Coast. Parekura told Mike that the response to Cyclone Bola was the best thing that had happened to the East Coast in his lifetime. He said everyone had a purpose, and everyone had jobs. There was massive clean up, and the young people were heavily involved. They had money in their pockets. They got a taste of what it was like to work, and they started to have ambitions. And he asked, ‘Why can’t governments create Cyclone Bola situations?’

***********

[1] Hon Sir Roger Owen Douglas, Minister of Finance, Lange’s Labour Government, 1984–1988, architect of a set of radical economic policies known as ‘Rogernomics’

[2] Boydie Donald, interview 26 May 2014

[3] Mum Jane (Smith) Waikari, Parekura’s grandmother, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tahu

[4] Alice (Tuppence) Smith, interview 20 March 2014, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tahu

[5] Poneke (Nunu/Duke) Waikari, Parekura’s grandfather, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou

[6] Te Huinga Kirikiri, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou

[7] Robert J. Gill, New Zealand Department of Labour, Occasional Paper Series, page 30

[8] Liz McPherson, notes, 29 April 2013

[9] www.gisborneherald.co.nz, 5 October 2007

[10] Ray Taylor, joined the Department of Labour in 1983; with Parekura, he coordinated the work force for Cyclone Bola recovery work in 1988

[11] Mike Williams, interview, 10 March 2014